A Pig's Year

Eat Issue 10: Pig

This article was originally published in April 2002.

They die so that we may live better. Paul Richardson sums up a year of pig-raising, at home in Spain.

JANUARY

Peaceful after the pig-killing of December, deep winter, for the pig-keeper, is a time of quiet satisfactions and laborious tasks. Laborious task number one: making the lard.

The leftover fatty bits go into a large aluminium pot. This is heated very gently all morning until a clear liquid appears among the solid lumps: this is ladled off into jars, where it cools to a pearly white cream.

There is no fat more out of fashion than lard. But used in moderation – to braise the first baby broad beans with bacon, or to fry up a couple of eggs over-easy – it is one of the best ingredients I know.

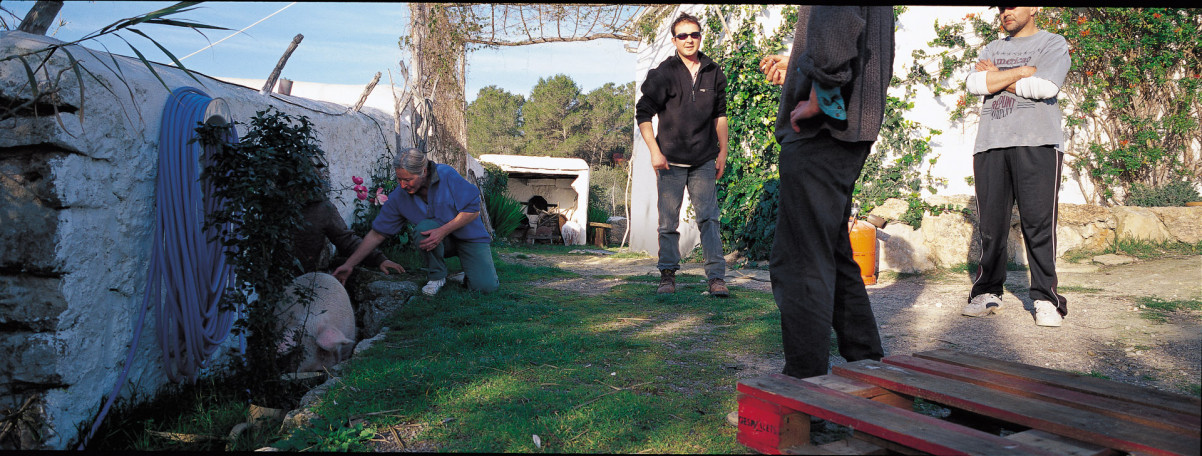

8am, killing day. Neighbours help coax the pig from its sty with the matancero, pig killer, standing by (arms crossed at right), and author appropriately dressed in black and sunglasses.

FEBRUARY

It is all too easy to forget that you have 50 kilos of pork in your freezer. Now is the time to get on with eating it, while the days remain cold and the body still thinks meat is a good idea.

Through my kitchen passes a parade of favourite dishes: pork chops with cider and apples, Chinese stir-fried belly with ginger and spring onions, choucroute garnie, barbecued spare ribs, and whole fresh chorizos grilled picnic-style on an open fire. Ultimate proof of the all-round usefulness of pigs is the soap that I make from rancid bacon fat.

Like most country tasks, this is a lot easier than you’d think. I found the method on the internet. The basic ingredients are fat (some people use olive oil, but pork fat gives a finer product) plus caustic soda, glycerine and fragrance. Oh, and plenty of time: soap-making takes all day.

MARCH

Spring cleaning: the empty pigsty must be mucked out. Not an agreeable task, you’ll agree, but ultimately a rewarding one. The manure is mixed with straw and left in a heap outside, ready to be dug into the vegetable patch along with the seedlings for the summer’s tomatoes, peppers, aubergines, courgettes.

The sty is now gleamingly clean, in readiness for its next occupant. I often think keeping a pig is like running a small residential hotel. With the difference that, as with the famous Roach Motel, your guests check in, but they don’t check out.

Hillside vegetable patch with lettuces and almond trees.

APRIL

And now for our next guest – a Middle White piglet weighing all of ten kilos, not long weaned from her mother, still small enough to climb into the trough with all four petite feet.

At first she is a bundle of nerves, scarpering into a corner at the first sign of human presence. Within a few days she will allow me to squat beside her and scratch behind her ears while she eats. Pigs learn fast. Within 24 hours she knows where she is to sleep, and where to find the en suite toilet.

Cute though she may be, however, she will remain nameless. It’s better for me that way. Miss Piggy (Miss P for short) is about as far as it goes.

MAY

Diet-wise, everything you have ever heard about pigs is true. They will eat practically anything apart from citrus fruit and anything from the onion family. This is not the same thing as saying they should be fed just anything.

My pigs are forbidden to eat meat, for example – though I do treat them to an occasional snail or juicy grub. Wild pigs eat them, after all. The ingredients of a typical pig’s breakfast chez moi might include: stale bread, boiled potato peelings, homegrown maize, eggshells and a whole egg or two, cabbage leaves, bruised apples and overripe pears, sour milk and other leftovers, all mashed up together into a rough muesli with a bit of barley flour and warm water. I could almost eat it myself.

She shrieks like a bathing beauty, racing delightedly around the sty before settling down to a good long scratch.

JUNE

Pigs are great in a glut. What else can you do with half a ton of rotting apricots? The same goes for the plums and cherries that grow around me, and, later in the year, figs and apples. A neighbour of mine keeps his pigs in a peach orchard. It comes as no surprise that his hams are sensational.

JULY

The temperature soars. Humans and pigs spend most of the Spanish summer slumbering in the shade. (Both species are pink and frazzle easily.) At least the pigsty is equipped with a retractable sun-roof made of palm fronds, providing a shady terrace upon which to doze away the afternoon.

In the cool of the evening, I will sometimes give Miss P a refreshing shower with the garden hose. She shrieks like a bathing beauty, racing delightedly around the sty before settling down to a good long scratch.

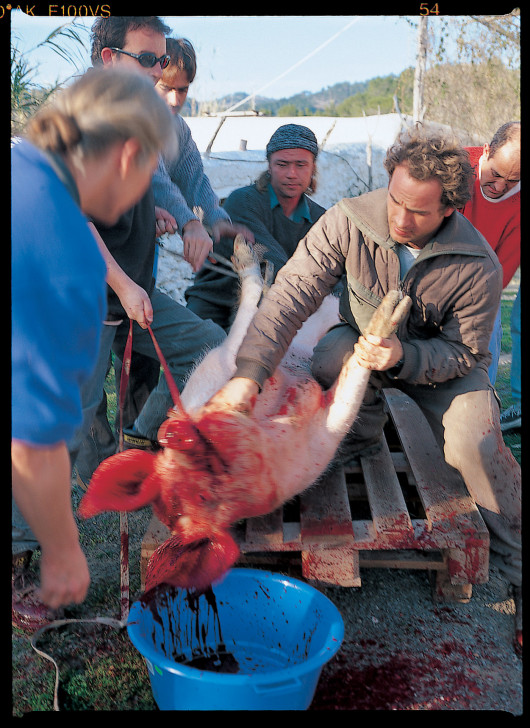

Bleeding the pig. The flailing body must be held firm by at least five people (four legs and the tail). Blood is stirred with the hand to prevent coagulation.

AUGUST

In the kitchen, these are summer days of gazpacho and ratatouille. Into the pigbucket, accordingly, go the skins of tomatoes and cucumber, the trimmings of aubergines and peppers. By the end of the summer when everyone is heartily fed up of courgettes, Miss P will be getting them whole by the basketful. She scoffs them as if they were Mars bars.

SEPTEMBER

With just a few months till the day of reckoning, Miss P is big and getting bigger. In six months she has ballooned from ten kilos to more than 100. No other animal puts on weight with the efficiency of the domestic pig – which is of course a major point in its favour.

Another is its ease of management. Looked after properly, pigs seldom get ill. It is only the crowded conditions, stress and poor diet of industrial meat production methods that bring about disease. Fresh air and exercise, plenty of tasty food, fresh water, and a crushed garlic clove sneaked into the feed from time to time (to keep down the worms) are all they need for a happy life.

Chorizo meat grinding. On trestle tables in the garage, one neighbour turns the handle while another piles in the meat. An old hand-grinder works best.

OCTOBER

Over the stone walls of the corral hangs a mighty specimen of Quercus suber, the cork oak. As the acorns ripen in autumn, they fall to the ground, whereupon the pig gobbles them up greedily.

The acorn (bellota) forms the dietary cornerstone of Spain’s most highly valued pig variety, the so-called Cerdo Iberico de Bellota. Highly valued because the acorn is a perfectly nutritious organic food source, making for gloriously aromatic, finely textured hams.

For the last few months of its life, the classic black-footed Cerdo Iberico subsists entirely on these acorns. For my spoiled pigs they are a luxury that falls from the sky.

NOVEMBER

The 11th, Saint Martin’s Day, traditionally marks the start of the pig-killing season in Spain. “A cada cerdo le viene su San Martin”, runs the proverb, which is roughly equivalent to saying “Everybody cops it in the end.” While the animal piles on its last few kilos, the owner stealthily prepares for the big day.

A range of ingredients must be laid up: several kilos of pimenton (for the chorizos), several more of coarse salt, ground black pepper and spices, a good plait of garlic. Knives must be brought to the requisite state of terrifying sharpness. A day is fixed, if possible under the calming eye of a waning moon (ancient belief says that the tumult whipped up by a waxing moon may spoil the meat). The services of a matancero (pig killer) are engaged. Friends are co-opted to help, for without plenty of help, none of this would be possible.

Do I feel sad at Miss Piggy’s violent death? Of course I do; just a little.

DECEMBER

Like all good executions, it happens at dawn. Strong cups of coffee, cigarettes and shots of hard liquor set the tone. The pig lumbers out of the sty and is shot through the head, collapsing instantly. It goes into spasms, and has to be forcefully held down while its jugular is cut to catch the still pumping blood. This is the goriest moment of a gore-filled day, though I prefer this method to the traditional way, which involves cutting the throat while the pig is alive.

As you might imagine, restraining a 150-kilo fighting pig is a tough proposition. The pig also squeals like hell. When it is all over, my first sensation is one of enormous relief. But then a curious thing happens. An animal you have cared for and cared about for the best part of a year, turns before your eyes into a large inanimate lump of meat, implying an infinite number of culinary possibilities and an immense amount of work.

I like to keep it as simple as possible, though for the purpose of sausage-making the intestines must be extracted and thoroughly cleaned – a major job in itself. Other than that, the pig gives me two hams (the hind legs), two shoulders, the loin and sirloin (which runs in a thick tube under the spine), the panceta (bacon), and plenty of spare ribs for barbecuing. The bones are salted and stored. After simmering the whole head in a giant copper pot the ears, cheeks, snout, and so on, are separated, finely chopped, mixed with spices, stuffed into a skin, pressed for several weeks, and eaten in cold slices. The delicacy is called, confusingly, cabeza de jabali – boar’s head. Any other spare meat goes into the chorizos, the bloodbased morcillas, and the English sausages, which I make with leek and sage.

Do I feel sad at Miss Piggy’s violent death? Of course I do; just a little. Though as winter turns to spring and my freezer slowly empties, I anticipate her reincarnation to appear at any moment. Outside the empty pigsty, the bloodstains will soon be washed away by the rain.

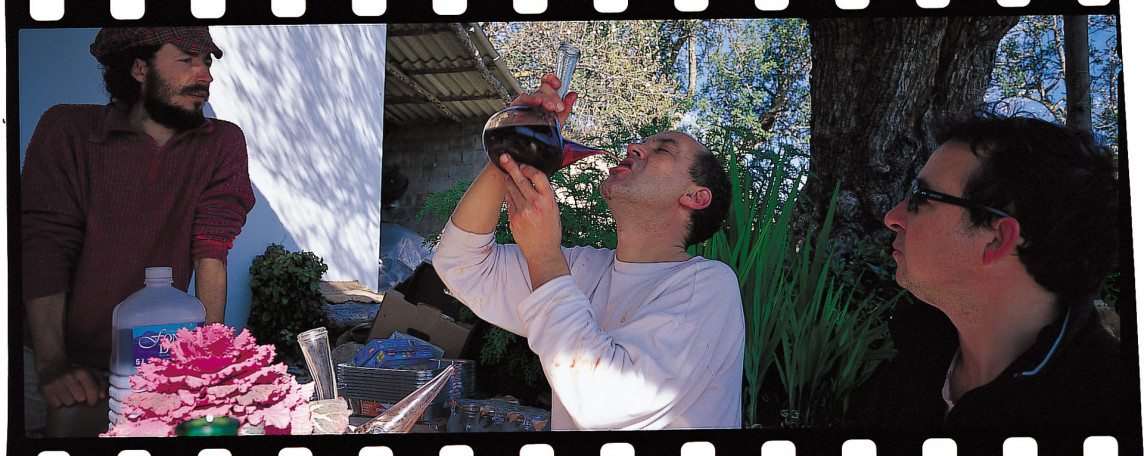

Post-killing Dionysian scene. A 500-year-old olive tree shades revellers drinking from a porron, or spouted carafe.

Text: Paul Richardson / Photo: Jason Lowe